The European Union and the United States seek to achieve four broad foreign policy goals in their relations with Serbia: contain Russia, contain China, normalize Serbia-Kosovo relations, and protect Bosnia’s sovereignty- of Herzegovina. However, for many years little progress has been made in any of these matters. Various reasons explain this, some within Serbia and others within Western capitals. EU and US policymakers could change this dynamic, but it seems unlikely that they will.

Western governments see Belgrade as an indispensable player in the major issues facing the Western Balkans. Whatever the issue at hand, the president of Serbia, Aleksandar Vucic, is the first person they call. Part of this practice is understandable: power in Serbia is concentrated in Vucic, who has acquired a significant portion of the powers for himself. And by any measure Serbia is the strongest country in the region. He enjoys enough political and economic leverage with unruly Serb politicians in Bosnia, northern Kosovo and Montenegro to rein them in when they cause trouble.

However, the achievements of Western governments are meager. Serbia has so far refused to participate in all rounds of EU sanctions against Russia and shows no signs of changing course in this regard. As an EU candidate country, Serbia is supposed to align with the bloc’s foreign policy positions – but its recent compliance in this area has dropped to just 45%, down from 64% in 2020. China’s influence on Serbia has increased rather than decreased, whether measured by investment, Chinese presence in the country’s critical infrastructure, or political and cultural ties. Serbia continues to support Milorad Dodik, the president of the Republika Srpska entity of Bosnia, whose actions and rhetoric threaten the country’s central government with destruction. As for Serbia and Kosovo, despite the hype surrounding a recent proposal from France and Germany, a viable solution remains unlikely. And on January 23 of this week, Vucic gave an hour-and-a-half televised speech, the content of which gives plenty of reason to doubt that he is participating in the negotiations in good faith.

Meanwhile, Vucic effectively controls the media in Serbia, whose influence severely limits the space for solutions to these problems, dissolving the options available to Serbia’s politicians – including his own. He has created an image in which the West is the enemy, while he himself struggles heroically not to bow to Western pressure to align with EU sanctions on Russia or offer concessions in Kosovo. This reason is reinforced by Russian TV operations in the country: the EU-approved Russian TV program started operations in Serbia in November 2022, while Sputnik has never stopped broadcasting there. Immediately following a meeting last week between Vucic and EU and US representatives on the Franco-German proposal, Sputnik broadcast Vucic’s Jan. 23 speech in which he expressed pride in resisting alignment with EU sanctions in Russia. The speech was marked by bad faith statements about Kosovo Prime Minister Albin Kurti and the EU and US delegations he had just spoken to.

Whether Brussels and Washington take all this into account is not obvious. Belgrade’s refusal to comply with EU sanctions has so far not had serious consequences for its relationship with either the EU or the US. The public rhetoric of EU and American officials towards Serbia continues to assume that Serbia is a reliable partner and factor in regional stability, despite any harsh words spoken behind closed doors.

In short, Vucic’s confidence that he can continue on his current course stems from the West’s continued failure to develop and exercise its potential advantage. Indeed, the president masterfully uses each of the key issues to shift the blame elsewhere for not doing what was agreed.

Recognition of Kosovo? Very difficult, given the right-wing nationalist opposition and public opinion (which Vucic helped shape the most). After meeting on the Franco-German proposal last week, he announced to the Serbian public that, thanks to him, recognition of Kosovo is off the table.

Dealing with secession in Bosnia-Herzegovina? It claims to do so, but portrays Dodik as welcome in Belgrade, including attending Serbia’s largest military exercises, which demonstrate Serbia’s military capability to defend “our country and our people.” Similarly, Serbia’s foreign minister is a regular guest at the January 9 anti-constitutional celebrations in Banja Luka, which commemorate a wartime initiative to unify Republika Srpska and Serbia.

Disconnection from Russia? He would like to, but 80% of the population of Serbia opposes sanctions against Russia – thanks in part to the media he controls which constantly broadcast pro-Russian messages. Ditto for China, which became the single largest investor in Serbia in 2022 and whose popularity in Serbia has grown exponentially, again due to government-controlled media.

A different approach: It’s possible but unlikely

There won’t be enough incentive for Serbia to change since there are no consequences for playing this way against the West. But the main obstacle lies both in the Western capitals and in Belgrade. When the going gets tough, Western officials seem unwilling to invest political capital in finding sustainable solutions to address the root of the problems. In private discussions, for example, many Western officials express the view that Serbia is doing “enough” for Ukraine and that the West should not push it further into the arms of Russia and China.

In theory, the EU and the US could approach it differently, using a dual tactic against Serbia – carrot and stick. Each side could accompany the commitment with the active use of political and economic pressure toward defined goals, such as an end to Serbia’s destabilizing policy of meddling in the affairs of neighboring states hosting Serbian minorities. But they should also be prepared to ensure that there are consequences for failing to achieve these goals.

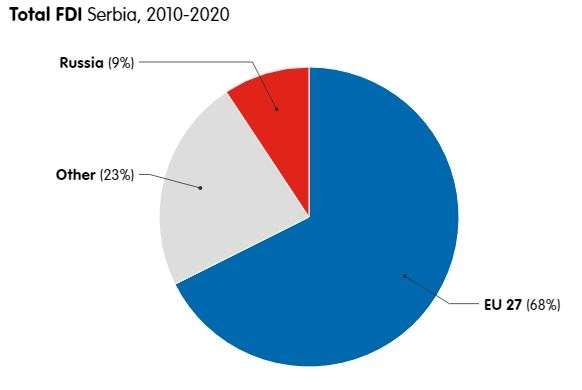

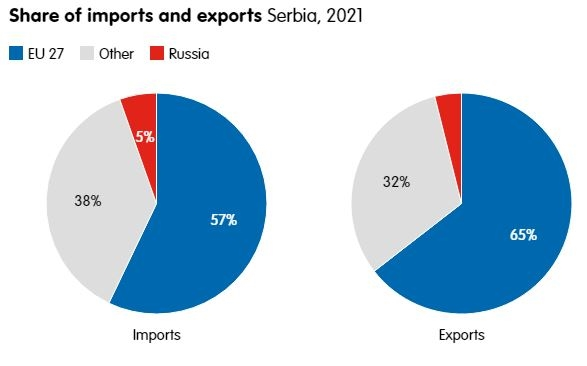

Both the EU and the US have a surplus of advantages over Serbia. Indeed, as the charts below show, Serbia is largely integrated into Western economic structures, conducting most of its trade with the EU and receiving significant foreign direct investment from the bloc. And while China’s importance has grown, its contribution to Serbia’s economy is insignificant compared to cumulative investment and trade from the EU. Russia is even less important – in 2021, 65% of Serbia’s exports went to EU and only 3% in Russia. EU investment continues despite Serbia’s poor foreign policy record.

More generally, key capitals such as Berlin and Washington could mount a sharper response to Vucic’s domestic anti-Western propaganda, raising the costs of its use. For example, EU and US officials could stop pushing him to address an audience every time they visit the region. Many sources over the years have suggested that the fear of losing would have an impact on Vucic’s behavior. Investing in something like this could be one of the keys to changing the relationship dynamic.

Let’s take another issue: a few weeks ago, Vucic publicly claimed that the EU threatened to abolish the visa-free regime and withdraw all investments if it did not accept the Franco-German plan. This is likely to be an exaggeration, given that the EU avoids using the visa-free regime as a threat and member states such as Germany claim that they do not have control over private investors. However, a tougher approach along these lines is exactly what is needed, alongside additional measures such as broader targeted sanctions against nationalist criminals who foment instability in the region and their political patrons.

Indeed, the broader approach still lacks the absolutely vital need to weaken the existing system of patronage that links government officials to secret networks, whether in Serbia or beyond its borders in northern Kosovo, Bosnia and Montenegro. Loosening the control of criminal networks in the state and improving the transparency of governance would cause a significant domino effect across the region, where the hostage-taking of the state by private individuals and criminality often hide behind destabilizing ethnic policies. The confusing jurisdictions and legal gray areas in Republika Srpska or northern Kosovo, which political leaders seek to legitimize by making demands for greater “ethnic autonomy”, allow organized crime to flourish and consolidate its control over the state. Bosnia’s post-Dayton history is replete with examples of the close relationship between crime and nationalist politics.

Western policymakers should study these cases carefully before considering constitutional models in northern Kosovo, such as the Union of Serbian Municipalities. They should also know that, for Russia and China, opaque and unassailable governance models provide ideal environments in which to operate. This issue should therefore be one of the first areas of action for Western politicians: solving Serbia’s and the region’s rule of law problems would make it harder for Russia and China to operate there and weaken ethno-criminal networks of influence in the Western Balkans.

All of this could be part of a new EU-US approach to the region, if key Western powers were indeed willing to adopt a longer-term framework and invest greater political capital. But for now, Western Balkan strongmen and wider connected networks will continue to have the freedom to destabilize the region – an integral part of their methods to maintain power and remain popular without accountability.

Source : Capital