Navigator CO2 Ventures has killed its proposed $3.5 billion, 1,300-mile carbon capture pipeline, slated to run across Iowa and four other states, citing “unpredictable” regulatory and government processes, especially in South Dakota and Iowa.

South Dakota regulators denied Navigator’s request for a permit in September, and the Omaha, Nebraska, company has twice pulled its permit application in Illinois, where it sought to sequester carbon dioxide.

Earlier this month, Iowa regulators agreed to let Navigator pause its permit request for an 800-mile stretch of the pipeline while it awaited regulatory action in Illinois.

“As good stewards of capital and responsible managers of people, we have made the difficult decision to cancel the Heartland Greenway project,” Matt Vining, CEO of Navigator, said in a statement posted on the company’s website Friday.

Navigator said it’s stepping away from “hundreds of millions of dollars” already invested to develop the project and pay landowners for pipeline route easements.

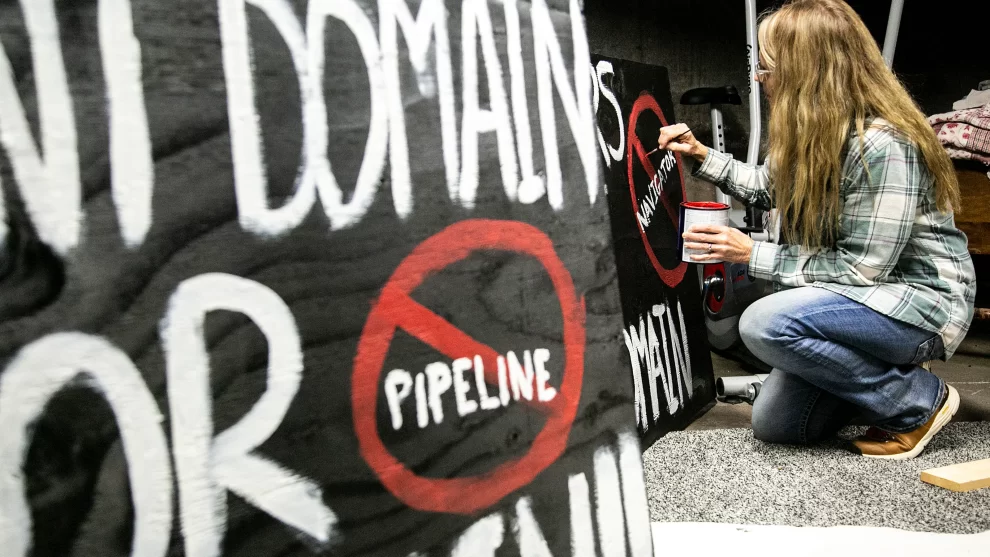

The announcement drew cheers from pipeline opponents, though two more companies — Summit Carbon Solutions and Wolf Carbon Solutions — are still seeking to build carbon capture pipelines in Iowa and other Midwestern states. The pipelines would transport the carbon dioxide emissions of ethanol and other plants, liquefied under pressure, to sites where the greenhouse gas would be sequestered deep underground.

“The people united to resist Navigator at every level, in every corner of every state, and we won,” said Jess Mazour, the Sierra Club’s Iowa Chapter conservation program coordinator. “We will continue our staunch opposition to carbon pipeline scams.

“The danger is not over. We have to stay vigilant and pass laws to make sure projects like this are not allowed in Iowa.”

Brian Jorde, an Omaha attorney representing landowners in Iowa and other states against the pipeline companies’ permit bids, called the decision “a monumental win for landowners.”

He said it was especially noteworthy considering the power and influence of Navigator investors like Valero Energy Corp., the Texas-based oil refiner, and BlackRock Inc. of New York, the world’s largest asset management company.

Jorde said the opposition the projects are hitting should send them a message: “If you haven’t been able to sell your project successfully by this point, it doesn’t deserve to exist.”

Will other pipeline projects continue?

Ethanol proponents stood by their contention that the pipelines are vital to American agriculture, providing a way to lower the carbon footprint of the ethanol industry, a huge buyer of the corn that states like Iowa grow. The Biden administration is offering billions of dollars in tax credits to incentivize carbon capture projects as it seeks to combat climate change.

“We know that carbon capture is the future for farmers, rural communities and our country,” said Tom Buis, CEO of the American Carbon Alliance, a carbon capture and storage advocacy group. “Just as bioethanol doubled farm income in the last two decades, carbon capture projects are the next step in bringing even more value to farmers nationwide.”

Ames-based Summit has encountered the same headwinds Navigator faced, and on Thursday pushed back two years to 2026 the timeline for making its pipeline operational. But it said Friday it was ready to sign on Navigator’s ethanol and other industrial agriculture partners, declaring it is “well positioned to add additional plants and communities to our project footprint.”

Jorde said he believes that will increase the pressure on landowners unwilling to sell easements to the carbon capture pipelines. “This ups the incentives significantly for Summit, with their No. 1 competitor waving the white flag … and there are billions of taxpayer dollars you can grab,” he said.

He questioned whether Navigator would sell its easement options to Summit. Elizabeth Burns-Thompson, Navigator’s vice president of government and public affairs, said Friday that language in the agreements “would allow for reassignment, but we do not have any plans to sell the pipeline easement options.”

States that block pipelines risk ‘being left behind,’ ethanol giant warns

Poet, the world’s largest ethanol producer, had planned to connect 18 plants, including a dozen in Iowa, to Navigator’s pipeline. It said Friday it would continue to pursue “viable technologies that help us maintain access to fuel markets and increase value for farmers.”

Not only is carbon capture seen as a way to keep ethanol viable amid the effort to limit global warming, it’s also seen as helping position the industry to make sustainable aviation fuel, a 100-billion-gallon annual market.

Poet said in a statement that carbon capture and sequestration is an “opportunity to transform rural economies and benefit farm families, much like the bioethanol industry has done over the past four decades.”

“We believe that states that are slow to adopt these technologies risk being left behind,” the Sioux Falls, South Dakota, company said.

Navigator’s Burns-Thompson said states across the pipeline’s footprint have treated permitting for carbon capture differently than for the crude oil, natural gas and ammonia pipelines many also have. In addition, state lawmakers have been discussing changes to the permitting processes, “creating even more uncertainty about what the future may hold,” she said in an email.

An especially hot topic has been the proposal to allow Summit and Navigator to use eminent domain to obtain easements for pipelines from landowners who won’t voluntarily sell them. Iowa lawmakers have discussed several bills over the past two years that would make it more difficult for companies to use the process.

Opponents also have voiced concerns about the pipelines’ safety and potential damage to farmland and the drainage tiles underlying it.

Monte Shaw, the Iowa Renewable Fuels Association executive director, blamed misinformation from environmental groups for the opposition the projects have encountered in Iowa and other states.

“That does not happen by accident. Rather, it is being pushed by groups who oppose modern agriculture and whose stated mission is to destroy farming as we know it,” Shaw said in a statement, adding that his group will continue to support multiple other carbon capture projects. “We expect ultimate success.”

But Summit faces hurdles to its $5.5 billion project. Like Navigator’s, Summit’s permit application was rejected in South Dakota, and the project also was turned down in North Dakota, where the company plans to sequester its carbon. It has said it intends to reapply in South Dakota and has won a request for reconsideration in North Dakota.

Navigator CEO says he’s proud of effort

Vining, the Navigator CEO, said the company is disappointed it will “not be able to provide services to our customers and thank them for their continued support.” In addition to Poet, Navigator also had an agreement with another large company, Iowa Fertilizer, in southeast Iowa.

Vining said he’s proud of the company’s efforts. “Our team maintained a collaborative, high integrity, and safety-first approach and we thank them for their tireless efforts,” he said.

In addition to Iowa, Illinois and South Dakota, Navigator’s 1,300-mile project also planned to reach into Minnesota and Nebraska.

Burns-Thompson said landowners who sold easements to Navigator will be able to keep the money they received.

Source : Des Moines Register